Machine ethics in autonomous vehicles: how decisions are encoded, issues in different cultures.

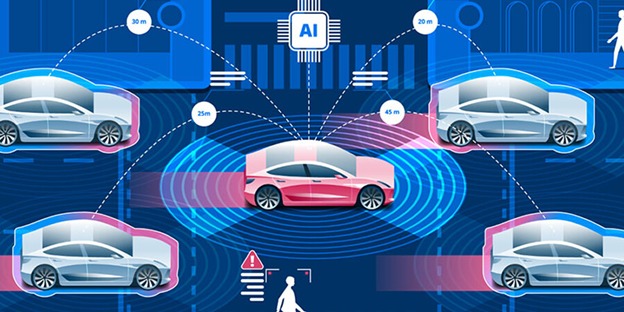

Autonomous vehicles are reshaping transportation, promising greater safety and efficiency, yet they face profound ethical challenges. Programming machines to make life-and-death decisions requires translating human moral judgment into algorithms, while accounting for cultural differences, societal norms, and legal frameworks. This article explores how AV ethics are encoded, the dilemmas involved, and the global challenges of culturally-sensitive decision-making.

✨ Raghav Jain

Introduction

The rise of autonomous vehicles (AVs) represents one of the most disruptive technological shifts of the 21st century. By removing human drivers from the equation, AVs are expected to reduce accidents caused by fatigue, distraction, and human error. However, their increasing autonomy brings with it a pressing challenge: machine ethics—the moral frameworks and decision-making rules encoded into the algorithms that control AVs.

When a human drives, decisions during an emergency—such as whether to swerve and risk the driver’s life or stay the course and endanger pedestrians—are often made instinctively and in split seconds. But an AV cannot act instinctively. Every choice must be encoded beforehand through algorithms, guided by ethical theories, laws, and cultural norms. This requirement forces society to confront ethical dilemmas that were previously left ambiguous, raising difficult questions: Whose safety should be prioritized? How should value be assigned to human lives in unavoidable accidents? Should rules be universal, or should they adapt to local cultures?

This article explores how machine ethics are programmed into AVs, the different ethical models under consideration, and how cultural differences create varied expectations worldwide.

How Ethical Decisions Are Encoded in Autonomous Vehicles

Encoding ethics in AVs involves translating philosophical frameworks into computational logic. This process is neither simple nor universally agreed upon. The main methods include:

1. Rule-Based Systems

In rule-based systems, AVs are programmed with explicit if–then statements reflecting laws and ethical guidelines. For example:

- If a pedestrian is detected at a crosswalk, stop immediately.

- If collision is unavoidable, minimize overall harm.

This method ensures transparency but struggles with complex, unforeseen dilemmas.

2. Utilitarian Algorithms

Derived from utilitarian ethics (maximizing the greatest good for the greatest number), these algorithms attempt to minimize overall harm in crash scenarios. For example, if forced to choose between one pedestrian and five passengers, the car might save the five. However, critics argue that such calculations reduce humans to numbers and fail to respect individual rights.

3. Deontological Models

Deontological ethics emphasizes rules and duties regardless of outcomes. An AV guided by this model might strictly follow traffic laws—even if doing so leads to worse consequences in rare cases. For instance, if swerving would save five pedestrians but require crossing a double line, the AV may refuse, because breaking the rule itself is unethical under this framework.

4. Virtue Ethics and Contextual Models

Virtue ethics emphasizes moral character and context, which is far more difficult to encode. Efforts here focus on adaptive AI that learns social driving norms (e.g., courtesy in yielding) through reinforcement learning and contextual cues. This model aims to approximate human-like moral intuition.

5. Probabilistic and Risk-Minimization Models

Some systems avoid philosophical frameworks altogether and instead use statistical models. These algorithms aim to minimize risk probabilities rather than make explicit ethical judgments. For example, an AV may prioritize braking power and speed reduction rather than calculating life trade-offs in emergencies.

In practice, most AV systems combine aspects of these approaches, balancing legal compliance, risk minimization, and ethical principles.

The Ethical Dilemmas in Practice

Autonomous vehicles face trolley-problem-style dilemmas, where harm is unavoidable but must be allocated. Common scenarios include:

- Passenger vs. Pedestrian Safety

- Should AVs prioritize their passengers (who purchased the car and trusted its safety) or pedestrians (who did not consent to risk)?

- Number of Lives

- Should one life be sacrificed to save many, or is every life equally valuable regardless of numbers?

- Law vs. Outcomes

- If breaking a traffic law avoids harm, should the AV do so?

- Protecting Vulnerable Groups

- Should AVs prioritize children over adults, or prioritize vulnerable road users (like cyclists) over car occupants?

- Predictive Ethics

- How should AVs act when outcomes are probabilistic rather than certain? For example, swerving may reduce risk but not guarantee safety.

These dilemmas are not only theoretical but are being actively studied through experiments like the Moral Machine project by MIT, which gathered millions of responses worldwide on AV dilemmas, revealing strong cultural differences.

Cultural Variations in Machine Ethics

One of the most significant challenges is that ethics are not universal. Different cultures hold different values regarding fairness, life, and responsibility. This complicates the creation of globally acceptable AV ethics.

Findings from the MIT Moral Machine Experiment

- Western countries (e.g., US, Europe): Preference for protecting younger lives and maximizing the number of lives saved.

- Eastern countries (e.g., China, Japan): Stronger emphasis on respecting elders and social roles.

- Latin American countries: Higher tolerance for risk-taking and sometimes preference for saving law-abiding pedestrians over jaywalkers.

- Middle Eastern countries: Stronger influence of social hierarchy in decisions.

Legal and Cultural Differences

- In Germany, laws explicitly forbid programming AVs to discriminate based on age, gender, or social role. Every life is treated as equal.

- In Japan, cultural respect for elders may influence public opinion toward protecting older lives.

- In the US, consumer liability is a major factor—buyers expect cars to prioritize their own safety.

- In India and developing countries, unpredictable traffic conditions and weaker enforcement of road laws create unique challenges for encoding ethics.

Collective vs. Individualistic Societies

- Collectivist societies (Asia, Middle East) tend to support utilitarian approaches that prioritize the greater good.

- Individualistic societies (US, Western Europe) often prefer protecting individual rights, including passengers who chose the AV.

Thus, AV manufacturers face a dilemma: Should they create universal ethical standards or adapt algorithms regionally to fit cultural norms?

Challenges in Implementation

- Legal Responsibility

- Who is liable when an AV makes an ethical choice that results in harm—the manufacturer, the programmer, or the owner?

- Transparency

- Algorithms must be explainable for public trust, but ethical logic is often complex and opaque in machine learning systems.

- Public Acceptance

- Consumers may reject AVs if they feel the car will sacrifice them for others, even if utilitarian models save more lives overall.

- Global Standardization

- International travel and commerce require AVs to operate across borders. Without harmonized ethics, conflicts may arise (e.g., an AV programmed in Germany behaving differently in India).

- Dynamic Contexts

- Unlike controlled lab settings, real roads are unpredictable, filled with human drivers, cyclists, jaywalkers, and cultural driving habits that algorithms struggle to capture.

Possible Pathways Forward

- Hybrid Ethical Frameworks

- Combine deontological rules (follow laws), utilitarian risk minimization, and cultural adaptations to balance universality with flexibility.

- Ethics-as-a-Service Platforms

- Governments or international bodies could regulate ethical decision-making modules, requiring manufacturers to adopt standardized ethical frameworks.

- Public Participation in Ethics

- Crowdsourcing projects (like Moral Machine) allow societies to shape the ethical rules of their AVs, increasing acceptance.

- Contextual Adaptation

- Use AI systems that learn cultural driving norms in specific regions, while maintaining core ethical baselines (e.g., equal human value).

- Transparency and Explainability

- Mandatory reporting and explainable AI techniques may build trust by showing how decisions are made in critical moments.

Autonomous vehicles (AVs) represent a revolutionary leap in transportation technology, promising to reduce accidents caused by human error, fatigue, or distraction, yet their development brings to the forefront one of the most complex and nuanced ethical challenges of the modern era: machine ethics. Unlike human drivers, who make instantaneous decisions based on instinct, experience, and personal moral judgment, AVs require every possible scenario to be pre-programmed into algorithms that guide their actions during both ordinary driving and emergency situations, forcing society to confront moral dilemmas in a computational framework. The process of encoding ethics into AVs involves translating philosophical and legal principles into decision-making rules, which is far from straightforward, as it requires reconciling competing ethical theories such as utilitarianism, deontology, and virtue ethics with real-world constraints and unpredictable traffic scenarios. Rule-based systems provide one method, in which AVs are programmed with explicit if–then instructions—for example, stopping immediately if a pedestrian is detected at a crosswalk or minimizing overall harm when a collision is unavoidable. While transparent, these systems struggle with novel or highly complex situations that fall outside predefined rules. Utilitarian models aim to maximize the greatest good for the greatest number, calculating which action results in the least overall harm. For instance, if an unavoidable crash risks one pedestrian versus five passengers, a utilitarian AV might choose to save the five, but this approach has been criticized for reducing human life to mere numbers, ignoring individual rights and moral dignity. Deontological models, on the other hand, prioritize adherence to rules and duties regardless of outcomes, meaning that an AV might refuse to break traffic laws even if doing so could prevent greater harm, highlighting the tension between rule-following and consequentialist reasoning. Other emerging approaches include virtue ethics and contextual models, which attempt to imbue AVs with a form of moral intuition, enabling them to adapt to social norms, courtesy-based driving, and situational ethics through machine learning and reinforcement learning algorithms. Additionally, probabilistic or risk-minimization models focus less on explicit moral reasoning and more on reducing overall accident risk through statistical analysis, adjusting speed, trajectory, and braking in uncertain conditions without necessarily making direct life-and-death calculations. In practice, most AV systems integrate elements of multiple frameworks, balancing legal compliance, risk mitigation, and ethical considerations, but even with these hybrid models, difficult dilemmas persist. Trolley-problem-style scenarios illustrate these challenges: should an AV prioritize its passengers or pedestrians? Should it minimize total casualties or treat each life as equally valuable? Should laws be strictly followed even if breaking them reduces harm? These questions are further complicated by predictive uncertainty—outcomes of split-second maneuvers are probabilistic rather than guaranteed—and by considerations of vulnerable populations, such as children, the elderly, or cyclists. Cultural variations significantly influence the public’s expectations of machine ethics, as evidenced by the MIT Moral Machine project, which gathered millions of global responses to AV ethical dilemmas. Findings revealed that Western countries often prioritize saving the young and maximizing total lives saved, reflecting individualistic and utilitarian tendencies, whereas Eastern countries like Japan and China may emphasize respect for elders and adherence to social roles, demonstrating collectivist ethical orientations. Latin American societies show a higher tolerance for risk and sometimes prioritize protecting law-abiding pedestrians over jaywalkers, while Middle Eastern responses indicate a stronger influence of social hierarchy on moral judgments. Legal frameworks reflect these cultural norms: Germany, for example, forbids programming AVs to discriminate based on age, gender, or social role, ensuring equal treatment of all lives; Japan may emphasize elder protection in line with cultural values; the United States often places liability and passenger safety at the forefront; and India faces unique challenges due to unpredictable traffic, lax enforcement, and diverse societal norms. These variations pose a major obstacle to creating globally acceptable ethical standards for AVs, especially when vehicles may cross borders with differing legal and cultural expectations. Beyond ethics, practical implementation raises questions about responsibility and accountability: who is liable when an AV makes a harmful choice—the manufacturer, the software engineer, or the owner? Transparency is another concern, as complex AI decision-making can be opaque, and public trust depends on explainable reasoning. Consumers may also be hesitant to adopt AVs if they fear that the vehicle will sacrifice their safety to protect others, highlighting the tension between safety statistics and perceived fairness. Potential pathways forward include hybrid ethical frameworks that combine deontological rules with utilitarian risk assessment, ethics-as-a-service platforms regulated by governments or international bodies, public participation in shaping ethical decision rules, context-aware adaptation of driving norms to local culture, and mandatory transparency in AI decision-making to build trust. Ultimately, the future of AV machine ethics likely lies in balancing universal principles—such as the inherent value of every human life—with cultural and regional adaptations that reflect societal norms, while ensuring that legal, technical, and ethical considerations converge to create vehicles that are not only safe but morally acceptable to the societies in which they operate. By embedding ethics into algorithms, AVs will need to navigate a world of probabilistic outcomes, legal constraints, cultural expectations, and public perception, ensuring that as machines take on greater autonomy, they do so in ways that align with both human safety and moral reasoning, illustrating that the path toward fully autonomous transportation is as much a journey through philosophy and culture as it is through technology.

Autonomous vehicles (AVs) are at the forefront of modern technological innovation, promising to revolutionize transportation by reducing human error, traffic accidents, and congestion, yet they introduce a host of complex ethical challenges that demand careful consideration, as every decision made by an AV must be encoded into algorithms rather than relying on human instinct or intuition, meaning that questions of morality, responsibility, and cultural norms must be translated into computational rules, a process that is far from straightforward and involves deep intersections of philosophy, computer science, and law; the field of machine ethics attempts to address these challenges by creating frameworks through which AVs can make morally-informed decisions in situations where harm is unavoidable, such as sudden pedestrian crossings, multi-vehicle collisions, or emergencies requiring split-second judgment, and this process generally relies on a combination of ethical theories, programming strategies, and risk-assessment models to guide the vehicle’s behavior, with approaches ranging from rule-based systems, which rely on explicit if–then instructions for predictable scenarios, such as stopping when a pedestrian is detected or maintaining lane discipline under traffic laws, to utilitarian algorithms that attempt to maximize overall benefit or minimize harm in accident scenarios by calculating outcomes and deciding, for example, whether sacrificing one individual to save several others is the morally correct choice, although utilitarian models are often criticized for treating human lives as numbers and for ignoring individual rights, while deontological models emphasize strict adherence to rules and duties, meaning that AVs programmed under this philosophy may refuse to break laws even if doing so would prevent greater harm, creating tension between rule-following and outcome-based morality, and more advanced models incorporate elements of virtue ethics or contextual decision-making, allowing AVs to adapt to social norms, interpret intentions of pedestrians or other drivers, and make ethically sensitive decisions based on situational factors learned through machine learning algorithms or reinforcement learning, further complicating the task of programming morality into autonomous systems; probabilistic and risk-minimization approaches complement these ethical frameworks by focusing on reducing the likelihood of harm using statistical models, braking patterns, trajectory adjustments, and adaptive speed control, without explicitly prioritizing moral values, providing a pragmatic layer that mitigates risk even when ethical calculations are uncertain, yet even with hybrid approaches combining these strategies, AVs face dilemmas akin to philosophical trolley problems, where choices between saving passengers versus pedestrians, prioritizing vulnerable populations like children or the elderly, or deciding whether to obey traffic laws versus avoiding imminent harm must be resolved in milliseconds, raising questions about liability, public trust, and societal acceptance, as passengers may feel uneasy knowing their safety could be sacrificed for the greater good, while pedestrians may expect AVs to yield to them regardless of passenger safety; cultural variation further complicates the encoding of machine ethics because values, norms, and priorities differ significantly between societies, as evidenced by large-scale studies such as the MIT Moral Machine project, which collected millions of responses worldwide regarding hypothetical AV ethical dilemmas, revealing that Western societies, including the United States and parts of Europe, tend to prioritize saving younger individuals and maximizing total lives saved, reflecting individualistic and utilitarian tendencies, whereas Eastern countries such as Japan and China emphasize respect for elders and social roles, demonstrating collectivist values, Latin American countries show a higher tolerance for risk and often prioritize protecting law-abiding pedestrians over those violating traffic norms, and responses from Middle Eastern regions indicate that social hierarchy and status can influence moral preferences, all of which illustrates that designing a one-size-fits-all ethical algorithm is virtually impossible without cultural adaptation; legal frameworks add another layer of complexity, with countries like Germany explicitly prohibiting programming AVs to discriminate based on age, gender, or social role, ensuring equality of life, whereas Japan’s cultural emphasis on elder protection may influence public expectations, the United States often prioritizes liability and passenger safety, and India faces challenges arising from dense, unpredictable traffic patterns, varying enforcement of road laws, and diverse societal norms, making it difficult for global AV manufacturers to reconcile ethical programming with both local legislation and cultural expectations, particularly as vehicles increasingly cross borders and encounter different driving behaviors and social attitudes; the question of responsibility remains unresolved, as liability for AV decisions may fall on manufacturers, software engineers, or vehicle owners, with legal systems still adapting to assign accountability in cases where encoded ethical decisions result in harm, and transparency becomes crucial, since complex AI algorithms are often opaque, and public trust depends on the ability to explain how and why AVs make life-and-death choices, a challenge compounded by the fact that probabilistic outcomes, machine learning adaptations, and real-world uncertainties make precise ethical reasoning difficult to convey; potential solutions involve hybrid ethical frameworks that balance legal compliance, utilitarian harm minimization, and cultural sensitivity, along with ethics-as-a-service platforms regulated by governments or international bodies to standardize moral modules, crowdsourcing public opinion to reflect societal norms in programming, dynamic context-aware learning systems to adapt driving behavior to local culture, and mandatory transparency measures that allow consumers and regulators to understand decision-making processes, all aiming to ensure that AVs operate ethically while maintaining safety, reliability, and trust; ultimately, the future of machine ethics in autonomous vehicles will likely rely on a careful balance between universal principles, such as the inherent value of all human life and adherence to fundamental traffic laws, and local adaptations that respect cultural expectations, social priorities, and public perceptions, acknowledging that ethical decision-making in machines is both a technological and philosophical endeavor, one that challenges society to consider how morality can be translated into code, how lives are valued differently across contexts, and how AI can be trusted to make decisions once reserved for humans, highlighting that the evolution of AVs is not merely a technological milestone but also a profound societal experiment, where culture, law, philosophy, and engineering converge to redefine transportation ethics in a rapidly changing world.

Conclusion

Autonomous vehicles represent both technological promise and ethical challenge. Encoding ethics into machines requires translating centuries-old philosophical debates into algorithms. While approaches range from utilitarianism to rule-based models, no solution satisfies all cultural expectations.

Global studies reveal significant cultural differences in moral preferences: Western nations often favor saving the young and maximizing numbers, while Eastern and collectivist cultures emphasize elders, hierarchy, and social duty. These differences make standardization difficult but highlight the importance of transparency and public participation in shaping AV ethics.

The future likely lies in hybrid frameworks: universal baselines ensuring equal respect for all human lives, with region-specific adjustments to reflect cultural norms. Ultimately, building trust in AVs will depend not only on safety performance but also on ensuring their ethical decision-making aligns with societal values.

Q&A Section

Q1: What is machine ethics in autonomous vehicles?

Ans: Machine ethics refers to the moral frameworks and rules encoded into the algorithms of autonomous vehicles that guide their decision-making in complex situations, especially during unavoidable accidents.

Q2: How do AVs make ethical decisions?

Ans: AVs use encoded models like rule-based systems, utilitarian algorithms, deontological rules, or probabilistic risk minimization. These frameworks help determine actions during emergencies, such as whether to prioritize passengers or pedestrians.

Q3: Why are cultural differences important in AV ethics?

Ans: Different cultures value life, hierarchy, and fairness differently. For example, Western societies prioritize saving more lives, while Eastern cultures may emphasize protecting elders. These variations make it difficult to design one universal ethical system for AVs.

Q4: Who is responsible when an AV makes a harmful decision?

Ans: Responsibility is still debated but may involve manufacturers, software developers, or vehicle owners, depending on legal frameworks. Many governments are working to establish clear liability laws.

Q5: Can AVs have universal ethics across all countries?

Ans: While universal baselines like equal human value may be achievable, cultural differences often require regional adaptations. A hybrid model balancing global standards with local norms is considered the most practical approach.

Similar Articles

Find more relatable content in similar Articles

E-Waste Crisis: The Race to Bu..

The rapid growth of electronic.. Read More

Virtual Reality Therapy: Heali..

Virtual Reality Therapy (VRT) .. Read More

The Future of Electric Planes ..

The aviation industry is under.. Read More

3D-Printed Organs: Are We Clos..

3D-printed organs are at the f.. Read More

Explore Other Categories

Explore many different categories of articles ranging from Gadgets to Security

Smart Devices, Gear & Innovations

Discover in-depth reviews, hands-on experiences, and expert insights on the newest gadgets—from smartphones to smartwatches, headphones, wearables, and everything in between. Stay ahead with the latest in tech gear

Apps That Power Your World

Explore essential mobile and desktop applications across all platforms. From productivity boosters to creative tools, we cover updates, recommendations, and how-tos to make your digital life easier and more efficient.

Tomorrow's Technology, Today's Insights

Dive into the world of emerging technologies, AI breakthroughs, space tech, robotics, and innovations shaping the future. Stay informed on what's next in the evolution of science and technology.

Protecting You in a Digital Age

Learn how to secure your data, protect your privacy, and understand the latest in online threats. We break down complex cybersecurity topics into practical advice for everyday users and professionals alike.

© 2025 Copyrights by rTechnology. All Rights Reserved.